Virtual Chat With Trufi Association

14 December 2020

Chatting Bus Data with MobilityData

17 May 2021Minibus in Djibouti. Photo courtesy of Tamara Kerzhner/World Bank.

On an unpaved road towards the outskirts of sprawling Lubumbashi, DRC, the minibus we were riding stopped between two fields. Still a kilometer from our destination, we stepped out into the road when the minibus unceremoniously made a U-turn and headed back towards the city center. Annoyed but entirely unsurprised, we walked the rest of the way.

In the absence of a transit authority, there’s nothing stopping a minibus driver from not completing their signposted route. In African cities, the competition to fill buses with passenger is often so intense, we assume crews must have a sense of the mobility needs of their passengers. Because they’re not encumbered with bureaucratic red-tape or based on top-down master plans, we expect that drivers are creating transport networks that reflect the demands of a constantly growing and changing city.

But, as more cities map their public transit, we see differences emerge: the scale and shape of the network, how it’s governed, and how well it actually connects riders to core opportunities. For some examples, and all the maps any urbanism geek could want, check out the work we did with the World Bank mapping access to jobs in 11 African cities, and looking at access to schools and health services.

How do we understand these differences? By assuming that these systems simply ‘react to demand’ we limit the possibilities for engagement, reform and improvement of working conditions and services.

What Map’s Hide

With khat and Coca Cola listed as operating expenses, it is not uncommon for Djibouti’s minibus drivers to work long into the port city’s hot summer nights. In a study with the World Bank, Transport for Cairo, and the University of Djibouti, we found some drivers clocking in as much as 20-hour workdays.

Particularly when we move the focus beyond the major African cities – Nairobi, Cape Town, Lagos and Accra – different patterns of financing, operations and regulations start to emerge.

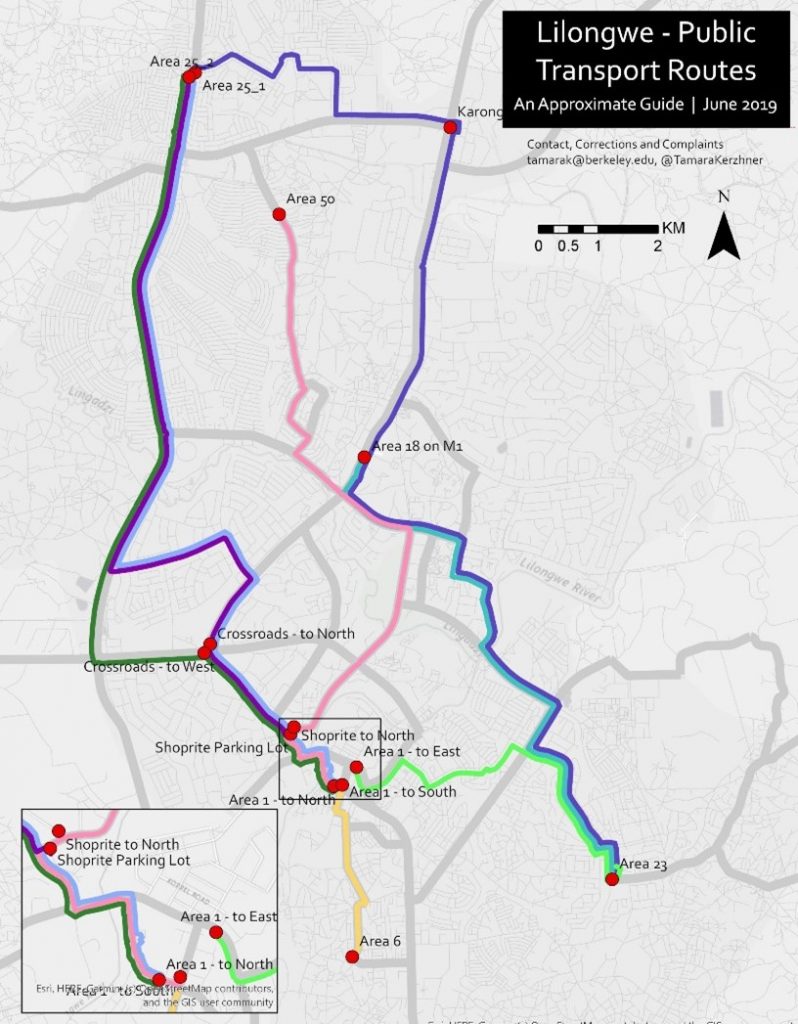

In Lilongwe, Malawi, a GPS mapping of bus routes shows huge areas of the planned, modernist city left without coverage. Passengers pay close to a dollar (600 Kwacha) to cross the city, in a country where the average monthly income is only 35 dollars per capita. Meanwhile, drivers struggle to make ends meet when they pay daily fees to lease the vehicle and for fuel and repairs, but receive only a lump sum from the bus owner at end of the month, in addition to keeping the meagre amount left of ticket sales.

In Lubumbashi, the second most populous city of the DRC, we identify over 60 distinct routes in work carried out with ROM Transport. But the routes typically converge on the central business district, favouring formal workers with downtown commutes, and offers little cross-connectivity between adjacent neig hborhoods. Who do these routes serve best? We know that women, for example, are more likely to work informal jobs and take more complex trips outside the central business district. For those living in the middle of one these routes, catching over-filled buses is near-impossible. To get into town, riders must ‘backtrack’ to the far-flung suburbs where these buses end their routes so they can hop on while they’re empty.

These challenges are impossible to capture on a map. But addressing them will start with the drivers, who are often the chief decisionmaker when it comes to drawing routes. As one might imagine, this is easier said than done.

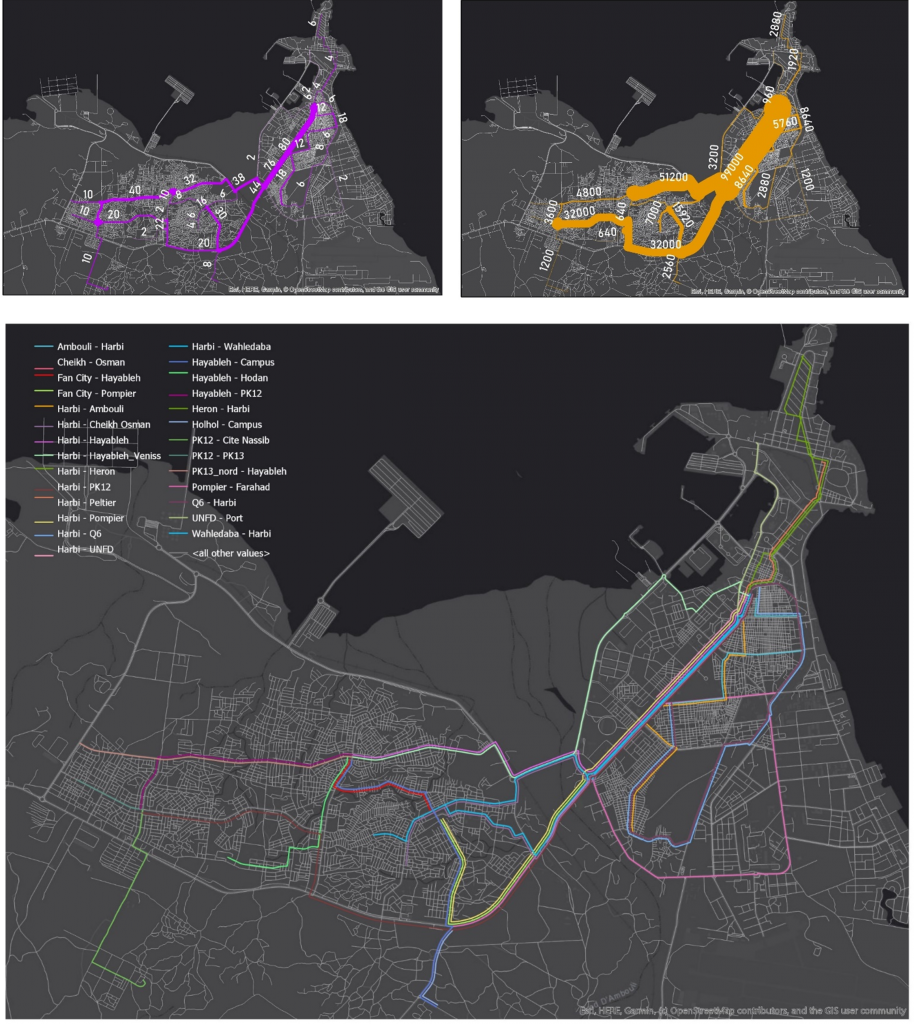

Djibouti – overall route network, number of buses operating per route, and ticket revenue per route.

Drivers as Transport Planners

When I ask drivers how they decide their routes and whether they change them – the answer is resoundingly that they don’t. In many cities, there’s nothing stopping drivers from choosing which route to operate on, but there are strong incentives to stick to the routes and passenger bases they know they can count on. In Lubumbashi, the daily fees of leasing and operating a bus are so high that missing out on just one full trip – minibuses make an average of 15 per day – would mean the workers take nothing home. The risks involved with scouting new passenger locations, destinations, and service niches that would expand the network is just not feasible under this type of contract.

Passenger demand plays a role in deciding a route, but this is hard to measure. As money changes hands from passengers to drivers to a myriad of other actors in the economic labyrinth that’s signature to public transit in African cities, keeping track of incomes and expenditures becomes a herculean task. The length of the route, traffic conditions and the quality of the road are also important factors when choosing destinations and are sometimes snap decisions drivers make in the moment. Forging a new route and establishing a passenger base also requires buy-in from dozens, sometimes hundreds, of independent bus operators. These complexities make developing new terminals and routes a slow, opaque process.

For instance, compare the overall route network of Djibouti, above, with the distribution of vehicles and passengers in the smaller maps. While coverage appears extensive, when looking at frequency across the city gaps start to emerge. After mapping routes, mapping the flows of passengers and profits is the next step. The fine-grained work of understanding the capacity, level of service, costs and workers’ preferences and incentives for serving different areas of cities is just beginning and is unique to each city. We require both better data, better understanding, and above all, greater collaboration and respect to fully engage with public transit operators.

From Reactivity to Planning

When transport workers and operators organize and unify, they can not only improve working conditions, but also the quality of services for passengers. Individual drivers do compete, but carefully. Crews are highly coordinated and can be mutually respectful, with strong management and rules, when it comes to operating on the same routes.

Planning public transit is neither bottom-up nor top-down – it’s the middle. Organizations, firms, cooperatives and associations can collectively manage terminals and routes, keep track of queues, balance the number of passengers and vehicles, and serve as a source of welfare and advocacy for drivers. But, more invisibly, it is also they who take initiative and make plans – transport plans.

In Nairobi, Savings and Credit Cooperatives Societies (SACCOs) were established in 2010 and require every vehicle to join an association which operates across specific routes. SACCOs actively test the waters of new destinations, measure demand, draw up maps, and make proposals to expand coverage. They can do this by pooling costs across multiple vehicles and subsidizing operations until a route is established. The network grows not by competition between drivers for passengers, but competition between SACCOs for routes.

Where workers remain fully individual in their operations they remain caught in the competitive spiral of exploitative working conditions that mean creating new and better services are punished, not rewarded. If cities want to reform and expand their public transit they need to start with the transportation workforce. Firms, associations, and unions are not the antagonists to the planning process, not even partners to be recruited. They’re already doing the work. Government regulators need to start by meeting them where they are.

About the Author

Tamara Kerzhner is a PhD student at the department of City and Regional Planning at the University of California, Berkeley. She has worked on a number of projects for the World Bank, NGOs and the public sector in Israel, Palestine, Djibouti, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and her dissertation research is a comparative study of transport planning in the informal sector in Malawi, Uganda and Kenya.