WatriFeed: The Open Source Collaborative GTFS Data Editor

17 May 2022

WRI and Partners Select 4 Winners for Digital Transport for Africa Innovation Challenge

14 June 2022“If you want to plan for all the facts, you’ll never end up going anywhere”

In Cape Town, South Africa, as in many African cities, planning a trip to a new destination by public transport is a piecemeal matter – not easily predicted in minute detail from home, but rather by doing and deciding along the way. Finding reliable information is a bit of a scavenger hunt. Routes for the trains might be available online, but unless you have a novel to get through while waiting for the train to arrive, you might want to check out your local WhatsApp group for up-to-date departure times. As for the minibus taxis, you’ll need to phone a friend or ask the driver.

With all the services available, public transport can get you pretty much anywhere in Cape Town. In theory. In reality, without adequate information, you can only get as far as your knowledge of the transport network allows. (Or your sense of adventure.)

There’s been a recent global push for the digitalisation of transport information in regions without prior recorded information. In such a context with little recorded information, but plenty of will power to collect the data needed, what information is useful to public transport users to navigate complex transport systems entailing both scheduled and unscheduled modes like minibus taxis and trains? Without any precedent of passenger information for hybrid systems or prior research done into what information users need for journey planning, how might we know what information to provide, and thereby which data to collect?

Needs as Capabilities

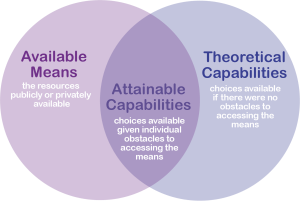

Figure 1. Access to means as attainable and theoretical capabilities

The capability approach is a valuable conceptual framework, for not only thinking about information as a means to an end, but also for breaking down the research approach to information provision. In a nutshell, the capability approach maintains that it is important to focus on expanding what people can achieve as opposed to what they end up achieving. If the emphasis is on what people do, then we fail to understand how a person’s decision may have been constrained by the choices available to them. For example, two students have access to a bicycle, but only one knows how to ride a bike to school whereas the other, despite having a bike does not know how to use it and needs to walk. In this vein, the capability approach can help elucidate how access to a means, like a transport system, is translatable into different mobility options dependent on an individual’s ability to convert the means into real journey choices. Information is a key component here in enabling individuals to understand the extent of their journey options and decide which option is best for them given their individual circumstances.

The capability approach can be used to define and break down the investigation process to uncover information needs and identify opportunities and barriers when disseminating information through technology.

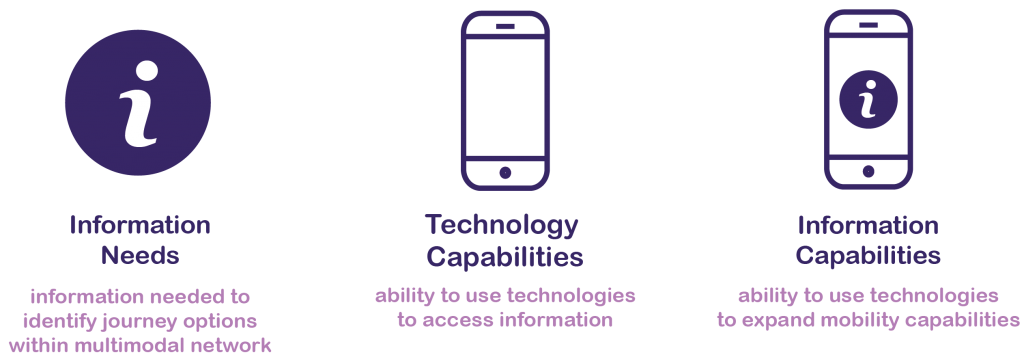

Figure 2. Amartya Sen’s capability approach applied to information and technology capabilities

Applying Information Capabilities to Cape Town

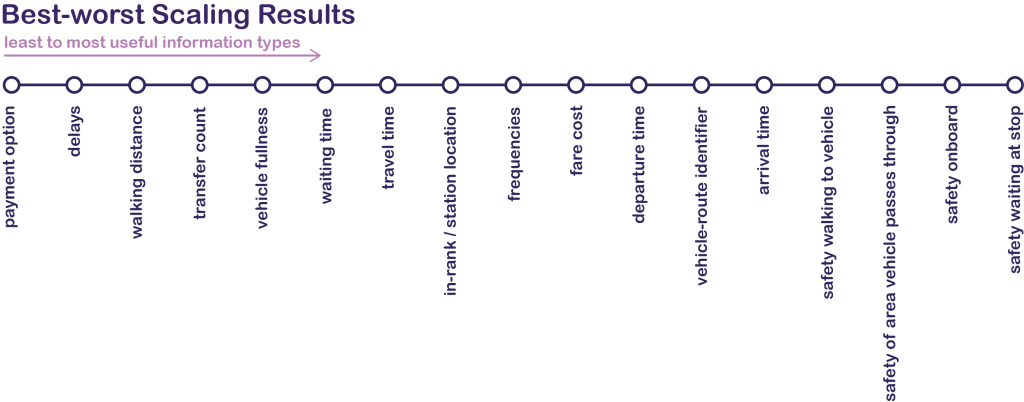

In Cape Town, we used this research approach to investigate the information needs of captive public transport users, or people without private motorised means of transport. We conducted individual interviews to create a comprehensive list of needs, followed by a best-worst scaling study to rank these needs from most to least useful, of which we took several of the most useful needs forward into a stated preference choice model survey to understand which of these information types were of most value and to whom in which journey context and whether this information needed to be real-time or not.

Figure 3. We only included information types that help make decisions between viable options, as opposed to core information like operating hours or stops which determine whether a journey is possible or not at a given time and place.

While to some extent, some of the information demanded was available in Cape Town, it was primarily limited to scheduled modes making hybrid journey planning cumbersome. One of the most significant findings was that across all transport environments – onboard, at the station, and walking to and from the station or stop – users demanded safety information.

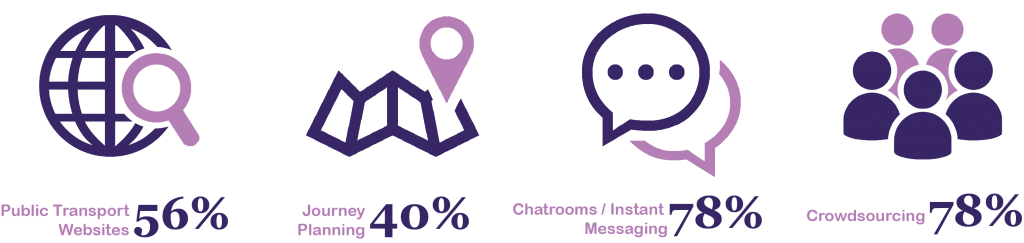

As for ICT abilities and access, we wanted to understand users’ capabilities not just in terms of whether they physically own a device (almost everyone does have a smartphone), but how comfortable they are using technology to tap into transport information to guide their decision-making. We asked users to self-report their ability to do various information-related tasks in Cape Town (a survey you can combine with the choice model) and supplemented this with secondary data from national surveys to identify trends in technology ownership. Though self-reported abilities aren’t necessarily the same as actual abilities, what the surveys did reveal is that traditional means of communicating transport information, such as via a map or timetable, aren’t necessarily the most accessible to users. This is perhaps not surprising given the familiarity with oral sources, like talking with drivers or asking friends, as compared to looking up public transport directions, especially given such apps are scarce in Cape Town.

Figure 4. Capabilities of captive public transport users to access transport information via mobile devices based on self-reported capabilities of common uses of information access in Cape Town (not factoring in unlimited access to mobile data)

Key Takeaways

What this research approach framed within capabilities revealed was that those assumptions we may have about which information is most important to users and their ability to tap into it are not universal truths. What may work in Portland, Oregon doesn’t necessarily translate well for Cape Town’s public transport users. Prior to designing a data collection strategy, know who your intended beneficiaries are and what their needs are. And if you do go the passenger information route, be mindful that for different user types, journey purposes, and stages of the journey these needs may differ. Be aware that data needed for one purpose will not necessarily fulfil those of another – the data needs of a transport planning agency are not guaranteed to also satisfy those of public transport users. The same is true when considering how best to put the information in the hands of users to enable them to make journey choices that maximise their capabilities. Once you understand passengers’ information needs, package this information such that it caters to passengers’ abilities to access and understand the contents well enough so that they really can plan for all the facts they need before they go somewhere using public transport.

About the Author

Bianca Ryseck is a Transport Studies PhD candidate at the University of Cape Town where she is investigating the role of information technologies in enabling equitable access to the hybrid public transport system in Cape Town. She holds MSc degree from the London School of Economics in City Design and Social Science where her passion for the relationship between social equity and urban development was born.