DigitalTransport4Africa (DT4A) at Sustainable Mobility and Climate Week 2022

26 September 2022

Highlighting the work of Digital Transport for Africa (DT4A) at the Sustainable Mobility and Climate Week 2022

27 October 2022Commuters waiting for the next bus desperately around Meskel Square – the city centre of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Photo by Agraw Ali

Long queues for public transport have become common sights during peak hours all over Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Under the hot sun or the heavy rain, people anxiously wait for the next public transport to arrive. Frustrated and eager to reach their destination, some passengers storm out of the line to try to see if walking might be a faster alternative, even if unsafe and inconvenient. If they are lucky, there might be a bus with an empty seat just across the street from where the long queues are, idly waiting for all the seats to fill up.

The lack of accessible, convenient and sufficient public transport is currently a burning political issue and city officials, including the Mayor of Addis Ababa, have promised citizens to put an end to the long queues. Unfortunately, these problems are not new to Addis Ababa alone as many African cities are facing similar issues. The dominant modes of public transport, their operations, and the level of inaccessibility may differ from one African city to another. However, there are strong similarities (in the root causes and impacts) that link them together.

Public transport challenges in African cities

The confluence of urbanisation and motorisation put cities in a dire situation to cope with the demand and pressure on resources, leaving many residents underserved and unable to access basic services. As many of these cities expand and add more traffic, residents are spending more money and time to get to their destinations, imposing huge costs on cities1. The same is true when it comes to infrastructure development. Unprecedented number of people reside in areas with limited or no access to convenient street and transport networks, while infrastructure investment and design are still skewed to benefit car users. More than 95% of road spaces in low- and middle-income countries are dedicated to cars, including on street parking2, leaving behind the low-income commuters that are highly dependent on walking, cycling, public transport and informal transport services.

Informal transport or minibus systems play a significant role in most African cities, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Informal transport systems are typically known for their flexibility, business model and dominance of second hand vehicles.These systems carry up to 95% of all public transport trips.3 Despite their importance, informal transport systems are not recognised in cities’ transport policies. This poses challenges to proactively engage informal transport operators to pursue a holistic operational reform to modernise and include them in a centrally planned system. While there are efforts made by local authorities to improve supply and alleviate the public transport challenges, the management and engagement with informal transport operators have been unsuccessful and, many times, the informal transport sector is not acknowledged and thus not integrated into transport plans and systems. To make matters worse, transport authorities in African cities often lack critical data for meaningful engagement, operational management and other decision making processes for informal transport, which has resulted in inefficient resource utilisation and ineffective interventions. These, coupled with insufficient governance capacity and lack of proper institutional setup, have been the main causes for strikes and distrust in government decisions. Recently, strikes took place in several African cities, including Johannesburg and Pretoria, Accra, Kampala, Kinshasa, Luanda and Addis Ababa, leaving many commuters stranded in taxi stations while others were forced to take long walks to their destinations.

How mapping public transport in Africa is important to meeting climate goals in the region

Improving public transport is the backbone of improving urban mobility as Africa’s cities grow. Focusing on informal transport is especially paramount as it is the most dominant (popular) form of public transport in many African cities. It can also be a place where policymakers and implementers can look to limit growth of carbon emissions and move people in ways that provide more access to jobs and opportunities, which goes in parallel with resolving challenges associated with providing basic infrastructure and attaining sustainable economic development.

An important starting point in unpacking and solving the challenges of informal transport in African cities is mapping of public transport. World Resources Institute (WRI), with support from the Agence Française de Développement (AFD), hosts the DigitalTransport4Africa (DT4A) initiative to map out public transport in Africa and establish ways to digitise transport as well as go beyond mapping to improve the quality of public transport services and identify climate-friendly pathways in the region.

Here are some ways mapping can unlock pathways to low carbon transport in Africa and why informal transport should be high on the agenda for climate action based on the Avoid-Shift-Improve approach:

1. Putting informal transport on the map and unlocking the power of transit data [Avoid/Reduce]

Acknowledging informal systems and their role over bridging the gaps of services provided by formal agencies – Adopting informal transport as a component of city-wide systems is paramount. Non-punitive strategies and plans should be formulated with informal transport in mind. Such strategies are essential to provide financial assistance for vehicle upgrading, corporatise operators and help operators organise themselves to bring accountability to both users and regulators.

Mapping is essential to improve public transport systems to avoid growth of private vehicle travel and the accompanying carbon emissions this would bring – Mobile applications that use route and service information data from mapping efforts provide better trip planning features which can help commuters find efficient ways to move around a city. Such applications could also enhance productivity of informal transport operators by better matching supply with demand. As a result, informal transport operators will have increased convenience and can easily get acceptance among users.

Identifying carbon emission of public transport – Mapping public transport in African cities can be used to establish inventories of carbon emissions from the sector and help inform how to create solutions that reduce emissions. The inventories can be generated from General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) datasets with open tools such as gtfs2emis, an R package that is being developed and soon be released by a research team at Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (ipea). Such tools will help cities to build scenarios and simulate the environmental impacts of different policies and interventions – such as fleet renovation and electrification. Public transport emission data is also critical to better study social inequalities in exposure to public transport pollution4.

2. Re-imagining public transport in African cities: From mobility to access for all [Shift/Maintain]

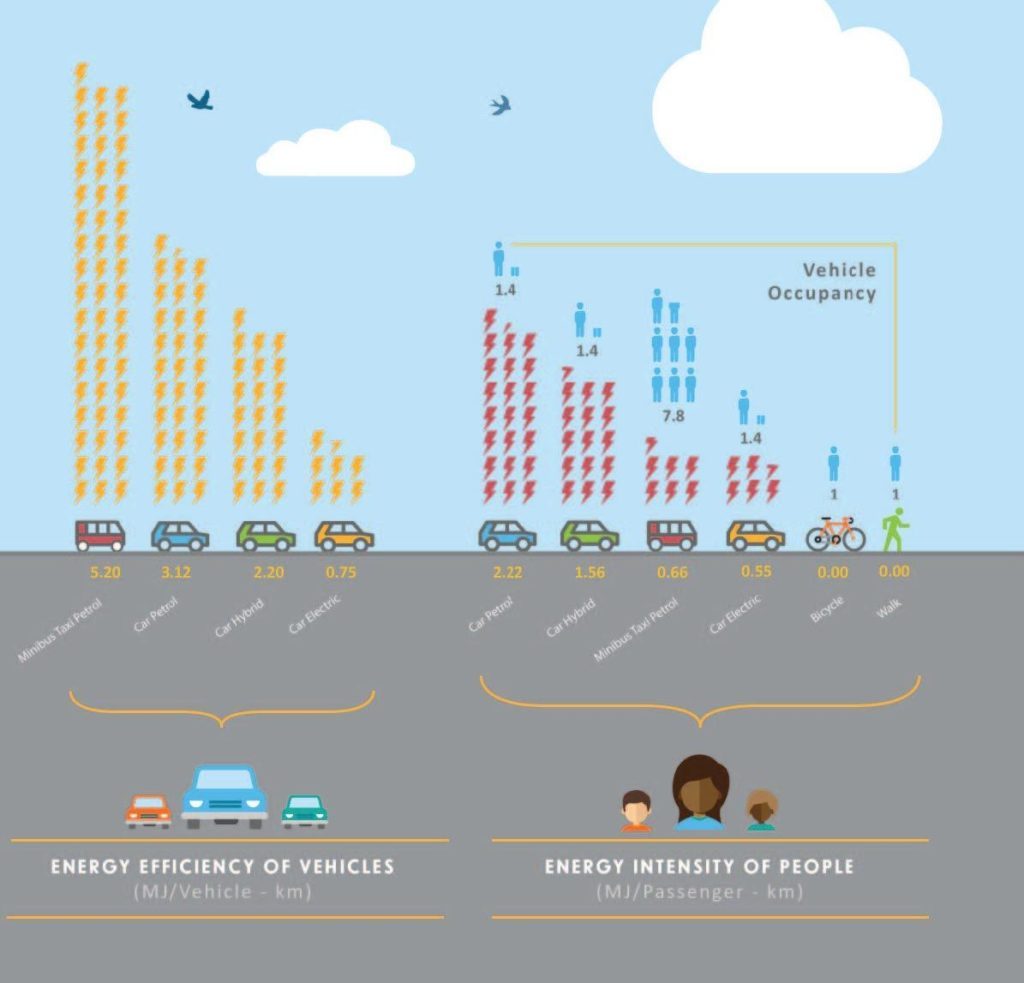

Using mapping as an entry point to improve the quality of minibus taxi services – Moving people through public transport (including informal transport) is more efficient. Minibuses use more energy compared to other vehicles on a vehicle-for-vehicle comparison, but such comparisons are misleading when it comes to efficiency of vehicles. According to a report for the city of Cape Town5, minibuses are more efficient and emit less emissions per passenger than private cars.

Vehicle-for-vehicle comparison of energy consumption versus energy efficiency of vehicles (Source: Lisa Kane 7)

Given the benefits gained from the carrying capacity of minibus taxis, mapping may be used to improve services and user experience, such as identifying route efficiencies, formalising stops and stations, providing routing information and real-time arrival.

Harness technology and data to integrate transit systems6 – Transit data helps in planning Bus Rapid Transit (BRT)services and integration of minibus networks. Continuous development of common standard formats like General Transit Feed Specification(GTFS), Realtime (GTFS-RT) and Flexible (GTFS-flex) offer opportunities to integrate transit operators in the formal and informal sectors while providing effective analysis and visualisation tools for planners and decision makers.

3. Electrification of informal transport [Improve]

Electrification of minibuses and introduction of larger capacity electric buses – apart from building policy scenarios to compare environmental impacts, several methodologies7 have been developed to model the performance of electric buses and minibuses based on standardised data collection. These approaches are also important to identify and prioritise operation routes for electrification. This would help the emerging minibus electrification efforts in Africa, such as the efforts of converting petrol minibuses to electric vehicles in Nigeria and introduction of electric matatus in Kenya.

Mapping can help inform the introduction of charging stations and routes – With a complete fleet operational dataset, cities would have options to investigate operational and business opportunities in current markets and plan for infrastructure necessary to implement electrification interventions. For instance, a South African company, GoMetro became one of the four awardees of the DT4A innovation challenge with a project that seeks to facilitate conversion from diesel to electric minibuses based on transit data.

Mapping as part of a broader strategy to engage more with the sector – One of the major factors hindering the implementation of better public transport infrastructure and service is a lack of good governance and well-planned projects. Governance being a key issue to address to electrify fleets, data on informal transport operators and even formal bus agency operations is critical to make attractive cases to build the confidence of development banks and financial institutions to invest in building the necessary infrastructures.8

COP27 – Quality Public Transport for Greener African Cities

Quality public transport can be key to providing solutions to Africa as cities grow, shifting away from more dependence on private vehicles and providing people more equal access to jobs and opportunities. Unfortunately, the informal or popular transport sector that dominates the motorised mode is non-existent in NDC commitments9. Mapping informal transport systems in Africa lays down a solid foundation to place public transport at the heart of transformative climate solutions in the transport sector. With the COP27 happening in Africa, the time is now to put it at the top of the sustainable, low carbon transport agenda.

Cross-posted from SLOCAT – African Voices Blog Series

About the Authors

Ben Welle is a Director of Integrated Transport & Innovation at WRI Ross Centre for Sustainable Cities. Ben’s work includes leading global research and projects, particularly in the areas of public transport, minibus services, mobility planning, access to opportunities, new mobility and innovation, traffic safety, walking & cycling, and public space. He has additional background in finance and positions in state government in the State of Minnesota, USA. Ben has a Master’s degree in urban and regional planning from the University of Minnesota and a bachelor’s degree from Hamline University, St. Paul, USA.

Iman Abubaker is the Urban Mobility Project Manager for WRI Africa, specifically working on improving livability of cities through integrated and equitable planning and safer street design. She works in coordination with city governments, local and international partners to research and implement sustainable and low carbon transport solutions particularly for African cities. She holds a M.S in Environment, Development and Policy from University of Sussex. She lives in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and enjoys cooking, travelling and “hygge” time with friends and family.

Agraw Ali is a GIS research analyst at the WRI Africa regional office. He works to present technical experience, analysis and administrative assistance to the WRI Africa Cities Program focusing on the scaling of transit mapping in African cities for improved transport planning. He holds a Master’s of Science in urban planning and design from the University of Seoul in Korea and a Bachelor’s of Science in Urban and Regional Planning from Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia.